Anne Hutchinson, puritan, wife, mother, midwife and top notch rabble-rouser. If you’ve never heard of her, it’s not your fault, probably… Anyway, I don’t know if she quite fits the bill for 17th century “girl boss,” but if she does, she may have girl bossed just a little too hard, as her story ends with tragedy. But let’s start at the beginning.

Anne Marbury wed William Hutchinson in 1612, about a year after the death of her father. Her father had been a Puritan Minister and staunch advocate of education, and she and her new husband were equally ardent and took up the torch upon his death. The young couple were drawn to the ministry of John Cotton, a rather unconventional voice in the Puritan movement in England, and John Wheelwright (Anne’s brother-in-law). Rev. Cotton found himself in hiding in England due to his peculiar beliefs, and ultimately would flee to Boston in 1633, to find safety in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Anne, William, and 11 of their 12 children would follow the following year; their oldest, Edward, went ahead with Rev. Cotton. (I’d get into the theology in detail, and why Cotton was such an oddball, but we’d be here forever.)

The large Hutchinson family settled into Boston life with relative ease. William, already a successful textile merchant, was welcomed into society, and took on a number of civic responsibilities. Anne devoted much of her time to assisting those who were ill or otherwise in need, and was an active midwife who was noted for her spiritual advice that she offered to the women she worked with. In the early years of their settlement in Boston, Governor John Winthrop would note that “her ordinary talke was about the things of the Kingdome of God,” and “her usuall conversation was in the way of righteousness and kindnesse.”

All was well for the Hutchinson family, in their large two story house in the heart of downtown Boston (located where the Old Corner Bookstore aka the world’s least-ergonomic Chipotle now stands). Anne began hosting informal meetings for local Boston women to discuss the sermons and reread scripture from the most recent service at First Church, where Cotton preached. And at first, she had the blessing of the local theological leadership. Again, Anne was a VERY educated woman, and had a pretty impressive knowledge of scripture, in large part due to her father’s career as a minister, and his belief in accessible education for all. Additionally, she was incredibly intelligent, as reported by almost everyone who wrote about her, including her later enemies. By all accounts up until this point, Anne was a model Puritan woman, she was charitable, pious, an excellent mother, nearly beyond reproach. So what went wrong?

Well, she started publicly criticizing the other ministers in Boston, and in front of MEN as well! Her informal scripture meetings eventually started to gain the interest of men in Boston, even the very powerful, such as the new Governor, Henry Vale. Her coed meetings continued to grow and draw more and more interest, and her “meetings” became events almost as popular as church on Sundays.

In the 17th century, this would have been somewhat unusual, but not necessarily a problem in itself. The conflict really reached a fever pitch when she began criticizing some Boston Ministers of preaching a “covenant of works” instead of a “covenant of grace”. This would blow up in a pretty big way, and become known as the Antinomian controversy, again, a topic worth its own post.

While it was a controversy in the old days, it may not seem like a huge deal to modern readers, but let’s try and make a mountain out this molehill to explain why everyone got so mad at Anne Hutchinson. Essentially, for Rev John Cotton, Rev John Wheelwright, and their followers, including Anne Hutchinson, salvation wasn’t something that could be earned. You had it or you didn’t, and your “intuition of Spirit” was the only thing that could decide that for you. Being a devoted and true believer was enough. It’s a much more personal and intimate relationship with scripture and God.

When Anne began accusing ministers in Boston of preaching a covenant of works, she was accusing them of misleading their congregations into believing that they could behave a certain way outwardly to receive salvation, without doing the internal work. Which implied they were unable to interpret scripture, and therefore either ignorantly stupid or evil. It was a pretty outrageous accusation to make, since most ministers would have disagreed. This was essentially the argument the original Protestants had used in their accusations against the Catholic Church.

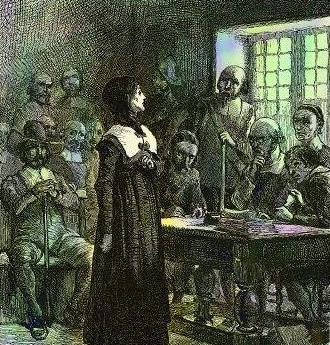

She also found disagreement with Reverends Thomas Shepard and John Wilson’s teaching, going so far as to get up and noisily walk out of services when Wilson got up to preach or pray, along with a number of her supporters. This behavior was so outrageous that in 1637 (3 years after she arrived in Boston), she was brought before the General Court of the Massachusetts Bay Colony (this is the equivalent of the house of representatives, and also assumed the role of a court that we would recognize today) on charges of slandering ministers. Over the course of two days, Anne defended herself by quoting scripture from memory to support her beliefs and refute the accusations against her, which made pinning her down really tough for the ministers arguing she was unqualified to speak about the correct interpretations. What they got her on in the end, is when she famously dropped this quote, which has often been reduced to the part about God talking directly to her:

“You have no power over my body, neither can you do me any harm—for I am in the hands of the eternal Jehovah, my Saviour, I am at his appointment, the bounds of my habitation are cast in heaven, no further do I esteem of any mortal man than creatures in his hand, I fear none but the great Jehovah, which hath foretold me of these things, and I do verily believe that he will deliver me out of your hands. Therefore take heed how you proceed against me—for I know that, for this you go about to do to me, God will ruin you and your posterity and this whole state.”

Many a scholar has written it off as a moment of hysteria or an exultant impulse, Which is the interpretation that I grew up with. However, others more recently, have interpreted it as pedagogy, which I find to be much more in character. Essentially, she treated everything like a teachable moment, and so she would use this to teach the judges in her case. At any rate, and regardless of intention, this dealt the fatal blow to an otherwise pretty shaky trial. Her statement was found to be seditious, and in contempt of court. She was placed under house arrest in the Roxbury home of Joseph Weld, where she would remain until her church trial the following March.

During the church trial, Hutchinson endured several days of interrogation, and chastisement eventually resulting in a forced recantation. For a moment, it seemed like she may have been able to return to her parish. Not satisfied with this, Shepard and Wilson brought up new issues, and this time, Anne would not recant.

By this point, most of her supporters and family had left to found a new settlement which they called Pocassett (what is now Aquidneck Island, Rhode Island). Ultimately,she was banished from the colony and she and her remaining supporters were given 3 months to leave the Colony permanently.

I wish Anne had a happy ending to her life’s story and got the last laugh. That is not the case. Anne was pregnant during much of this ordeal (as she was for much of her adult life), and in her mid forties. In May of 1638 she delivered what was described as “a transparent bunch of grapes,” and has been thought to be a molar pregnancy. The Massachuestts colonial leadership would mercilessly gloat over her misfortune.

The Pocassett settlement would suffer a political rift, eventually separating into two towns, Portsmouth and Newport. Massachusetts Bay then threatened to annex the Narragansett Bay area shortly after her husband’s death in 1641. In 1642, fearing further persecution, she would move with 7 of her children, a son-in-law and several servants to New Netherland, in what is now the northern part of the Bronx in New York. In 1643, Anne and her children became casualties of Kieft’s War between European settlers and local Indigenous tribes. During a raid, the entire family, with the exception of one daughter (who was taken captive by Siwanoys) would be killed.

The ministers of Boston would never let her live in peace as long as she lived in New England. The entire time she lived in Portsmouth, laymen would be sent to try to convince her of her errors, to which she is said to have responded on one occasion, “the Church at Boston? I know no such church, neither will I own it. Call it the whore and strumpet of Boston, but no Church of Christ!” Get ‘em girl.

More Blogs

- Boston Historical Tours

All Blogs Hat Tip to the LOLs The remarkable tale of Margaret Hamilton is one of the highlights of our Innovation Tour. Hamilton was Director of Software Engineering for NASA’s Apollo program.

- Boston Historical Tours

All Blogs Hat Tip to the LOLs The remarkable tale of Margaret Hamilton is one of the highlights of our Innovation Tour. Hamilton was Director of Software Engineering for NASA’s Apollo program.

- Boston Historical Tours

All Blogs Dickens and a Christmas Carol Come to Boston A long time ago, longer than I would care to admit, I was asked to develop a Christmas themed tour for a

- Daniel Berger-Jones

All Blogs Anne (Marbury) Hutchinson Anne Hutchinson, puritan, wife, mother, midwife and top notch rabble-rouser. If you’ve never heard of her, it’s not your fault, probably… Anyway, I don’t know if she